Po rządach ostatniego Sasa Rzeczpospolita była mocno osłabiona – opozycja magnacka odżyła i utrzymała „liberum weto”. Dzięki temu mogła jednym głosem paraliżować prace sejmu albo nawet zerwać sejm. W 1764 roku Caryca Katarzyna II oficjalnie zarekomendowała młodego stolnika litewskiego na króla Rzeczypospolitej Obojga Narodów a wolna elekcja odbyła się w asyście wojsk rosyjskich. Od tego momentu rządy króla Stanisława Augusta miały przebiegać pod stałą kontrolą Rosji. Król okazał się jednak „niepokorny”, bowiem od początku panowania przyświecała mu myśl reformy państwa i odbudowy Rzeczypospolitej.

Pod koniec lat 80. XVIII w. Stanisław August Poniatowski wraz z obozem patriotycznym podjęli kolejną próbę przeprowadzenia reform. Wykorzystali sprzyjającą sytuację polityczną – w 1787 roku Rosja została zaatakowana przez Imperium Osmańskie i wybuchła wojna rosyjsko-turecka. U boku Rosji przeciwko Turcji wystąpiła Austria. Katarzyna II rozpoczęła starania o pomoc zbrojną Rzeczypospolitej przeciw Turcji, formalnie zgadzając się, między innymi, na wzmocnienie władzy królewskiej w Polsce oraz na zwołanie sejmu pod węzłem konfederacji. Oznaczało to, że decyzje mogły zapadać większością głosów. Marszałkiem został Stanisław Małachowski, jeden z przywódców obozu reform.

1) Portret króla Stanisława Augusta Poniatowskiego, malarz Johann Baptist Lampi, domena publiczna / Portrait of King Stanisław August, painted by Johann Baptist Lampi, public domain.

Prace nad Ustawą Rządową rozpoczęły się we wrześniu 1789 roku podczas trwania Sejmu Czteroletniego, zwanego Wielkim. Opracowanie reformy ustroju było pracą zespołową. Pieczę nad reformą sprawować miała uchwalona przez sejm „deputacja do poprawy formy rządu”, kierowana przez biskupa kamienieckiego Adama Stanisława Krasińskiego. Faktycznym przywódcą deputacji był jednak marszałek nadworny litewski – Ignacy Potocki. Potocki pisał projekty reform, a następnie konsultował je z pozostałymi członkami komisji. Prace deputacji przebiegały jednak wolno. Pierwsze projekty nie wzbudzały euforii wśród zgromadzonych posłów. W sierpniu 1790 roku deputacja przygotowała nowy projekt złożony z 11 części, obejmujący 700 artykułów.

Równolegle w latach 1790-1791 zaczęły powstawać projekty na tajnych posiedzeniach, odbywających się w domu księcia Adama Czartoryskiego. Brali w nich udział Ignacy Potocki, Stanisław Małachowski, Scypion Pitattoli, Hugo Kołłątaj, Aleksander Linowski, Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz, Józef Weyssenhoff i Aleksander Lanckoroński. Zaangażowanie króla do prac nad reformą nie było proste, bowiem zespołowi przewodniczył jego główny opozycjonista – Ignacy Potocki, który odsuwając animozje na bok, zdecydował się osobiście poprosić Stanisława Augusta o poparcie. Król przystąpił do prac już w grudniu 1790 roku, aprobując wiele pomysłów Potockiego, wprowadzając też własne korekty. Debaty nad ostateczną wersją Ustawy trwały do ostatniej chwili. Zdecydowano jednak zaprezentować ją w sejmie 3 maja 1791 roku. Przeciwnicy projektu zgromadzili się u ambasadora rosyjskiego, debatując jak nie doprowadzić do uchwalenia reform.

W dniu czytania Ustawy do obrony reform przygotowane były zawczasu gwardie królewskie i regiment piechoty im. Działyńskich. Z arsenału wyprowadzono nawet armaty. Galerie na sali sejmowej wypełnione były po brzegi. Nie obyło się bez ekscesów, jak choćby dobitnie wyrażanego sprzeciwu posła Suchorzewskiego, którego musiano siłą postawić na nogi. Ostatecznie król zaprzysiągł Ustawę słowami: „Juravi Deo et non poenitebit me…” (Przysięgam Bogu i żałować tego nie będę…) i wezwał zebranych, aby udali się z nim do katedry św. Jana, gdzie złożył przysięgę ponownie.

2) Konstytucja 3 Maja 1791 roku, malarz Jan Matejko, 1891, domena publiczna / May 3rd Constitution 1791, painted by Jan Matejko, 1891, public domain.

Konstytucja 3 Maja, zwana Ustawą Rządowa, składała się z 11 artykułów. Była pierwszą w Europie i drugą na świecie, po konstytucji amerykańskiej, ustawą regulującą organizacje władzy państwowej oraz prawa i obowiązki obywateli. Brała pod uwagę nie tylko szlachtę, ale także mieszczan i chłopów. Ograniczała prawa szlachty nieposiadającej dóbr, tzw. gołoty. Szlachta ziemiańska, posiadająca majątki, wciąż utrzymywała swoje przywileje i zwierzchnictwo nad chłopami, ale w ograniczonej formie. Chłopi nie uzyskali swobód politycznych, tylko zapewnienie o ochronie rządu i prawa, chociaż utrzymano pełną zwierzchność szlachty nad chłopem. Ustawa zapewniała wolność osobistą osadnikom z zagranicy i zbiegłym poddanym. Zapowiedziano tolerancję religijną – zaznaczono jednak, że religia rzymsko-katolicka jest panująca. Konstytucja scalała Polskę i Litwę. Zlikwidowane zostały odrębne instytucje państwowe na Litwie, konstytucja wprowadzała wspólną armię i wspólny skarb, a szlachta litewska uzyskała prawo do obsadzenia połowy stanowisk w organach centralnych.

Wprowadzono po raz pierwszy pojęcie narodu – obywatele mieli być obrońcami swobód narodowych i praw, a projekt stworzenia 100-tysięcznej armii polskiej przyjęty został przez aklamację. Na czele armii „siły zbrojnej narodowej” stał król. Wprowadzono zakaz posiadania prywatnych wojsk.

Na podstawie Konstytucji 3 maja Rzeczypospolita stawała się monarchią konstytucyjną. Władzę ustawodawczą sprawował sejm i wciąż pozostawał on najważniejszym organem władzy. Miał być zwoływany przez króla lub marszałka. Większość posłów stanowiła szlachta – na 204 deputowanych w komisjach sejmowych zasiadało jedynie 24 przedstawicieli mieszczan. Wszystkie uchwały miały zapadać większością głosów, zostało zniesione „liberum veto”. Likwidowano również konfederacje i rokosze – zbrojne wystąpienia szlacheckie.

Sejm miał być „zawsze gotowy”, co oznaczało, że podczas swojej dwuletniej kadencji posłowie mogli być zwoływani na sesje nadzwyczajne. Konstytucja ograniczała prawa senatu, pozostawiając mu jedynie prawo weta w stosunku do uchwał sejmowych. Do kompetencji sejmu należało ustawodawstwo i uchwały podatkowe oraz kontrolowanie rządu i uchylanie jego decyzji. Ustawa zasadnicza zmniejszała także zależność sejmu od sejmików. Co 25 lat miał zbierać się specjalny sejm konstytucyjny i rewidować konstytucję.

Władzę wykonawczą sprawować miał król wraz z mianowanym przez siebie gabinetem ministrów, nazwanym Strażą Praw, w skład której wchodzili król, prymas i pięciu ministrów: policji, pieczęci (spraw wewnętrznych), wojny, skarbu, spraw zagranicznych, następca tronu i marszałek sejmu z głosem doradczym. Ministrowie mogli być powoływani przez króla spośród najwyższych urzędników tylko podczas obrad sejmowych. Sejm mógł się nie zgodzić na kandydata króla i miał prawo zażądać większością 2/3 głosów odwołania ministra lub postawienia mu wotum nieufności. Każdy akt wychodzący w imieniu króla miał być przygotowywany przez Straż Praw i podpisywany przez odpowiedniego ministra. Ustawa znosiła odpowiedzialność monarchy. Od tej pory przed sejmem mieli być odpowiedzialni ministrowie. W przypadku władzy sądowniczej najwyższym organem sądowym pozostawał Trybunał Koronny i Litewski. Utworzono sądy magistrackie dla miast oraz sądy apelacyjne.

Rzeczypospolita stawała się również monarchią dziedziczną. Jako że król nie posiadał oficjalnie ani żony, ani potomka, po Stanisławie Auguście tron miał przypaść Fryderykowi Augustowi Wettinowi, potomkowi dynastii wcześniej panującej w Polsce – Augusta III Sasa. Zakładano bowiem, że w ten sposób zdoła się ograniczyć ingerencje obcych państw w sprawy polskie.

Konstytucja, nie zmieniając w sposób zasadniczy charakteru państwa i biorąc pod uwagę interesy bogatego mieszczaństwa, stanowiła ważny krok na drodze do rozwoju państwa nowożytnego. Mieszczanie miast królewskich utrzymywali, zapewnione wcześniejszym dekretem: prawa i wolności polityczne, gwarancję nietykalności osobistej, prawo do nabywania i dziedziczenia ziemi, dostęp do urzędów i stopni oficerskich, prawo do nobilitacji (nadanie szlachectwa), własny samorząd i prawo do reprezentacji sejmowej (plenipotentów).

Konstytucja 3 maja stanowiła największe dzieło Sejmu Wielkiego i do dnia dzisiejszego uważana jest za jeden z najważniejszych aktów prawnych w dziejach Polski. Jej uchwalenie spotkało się z dużym oddźwiękiem. Dawała nadzieję na przeprowadzenie reform w kraju i suwerenność. Nie zyskała jednak aprobaty wśród konserwatywnej bogatej magnaterii, która chciała powrotu do dawnych struktur, a nawet myślała o podziale Rzeczypospolitej na autonomiczne prowincje. Poza granicami Konstytucja traktowana była jako przejaw bezkrwawej reformy państwa, podczas gdy we Francji monarchię obalono siłą i trwała rewolucja.

Ustawa Majowa nawiązywała do ideologii Oświecenia i teorii społeczno-politycznych, głównie francuskich filozofów: Monteskiusza i Rousseau. Ustanawiała trójpodział władzy: władzę prawodawczą, wykonawczą i sądowniczą. Znosiła wyłączne prawo szlachty do posiadania ziemi i pełnienia urzędów. Likwidowała przyczyny anarchii gnębiącej Rzeczpospolitą, takie jak: liberum veto, wolna elekcję oraz odwieczne prawo szlachty do rokoszu i konfederacji.

English version

“I swear to God and I will not regret it. . . ”

May 3rd – 230th Anniversary of the Adoption of the May 3rd Constitution

After the reign of the last Saxon king (Augustus III), the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was strongly weakened – the wealthy magnate opposition revived and maintained the “liberum veto”. Thanks to this, it could paralyze the work of the Sejm (parliament) with one dissenting vote or even terminate it. In 1764 Tsarina Catherine II (Catherine the Great) officially recommended the young nobleman Stanisław August Poniatowski as King of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and the free election took place with the assistance of Russian troops. From that moment on, the rule of King Stanislaw August (Stanislaus II Augustus) was to be under the constant control of Russia. However, the king turned out to be “rebellious” because from the beginning of his reign he was guided by the idea of reforming the state and rebuilding the Polish Republic.

At the end of the 1780s, Stanisław August Poniatowski, together with the patriotic camp, made another attempt to carry out political reforms. They took advantage of the favorable political situation – in 1787 Russia was attacked by the Ottoman Empire and the Russo-Turkish War broke out, with Austria taking the side of Russia against Turkey. Catherine II began efforts to obtain military assistance for the Polish Republic against Turkey, formally agreeing, inter alia, to strengthen royal power in Poland and to convene a parliament under the bond of a confederation. This meant that decisions could be made by a majority vote. Stanisław Małachowski, one of the leaders of the reform camp, became the Marshal of the Sejm.

Work on the Government Act began in September 1789 during the Four-Year Sejm, known as the Great Sejm. The development of regime reform was to be a team effort, supervised by a “delegation to improve the form of government” passed by the Sejm and headed by Adam Stanisław Krasiński, Bishop of Kamieniec. However, the de facto leader of the delegation was the Marshal of the Lithuanian court, Ignacy Potocki. Potocki wrote draft reforms and then consulted with the other members of the commission. However, the work of the commission proceeded slowly. The first drafts did not inspire euphoria among the assembled deputies. Then in August 1790, the delegation prepared a new draft comprised of 11 sections, including 700 articles.

At the same time, in 1790-1791, drafts began to be drawn up at secret meetings held at the home of Prince Adam Czartoryski. These were attended by Ignacy Potocki, Stanisław Małachowski, Scypion Pitattoli, Hugo Kołłątaj, Aleksander Linowski, Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz, Józef Weyssenhoff and Aleksander Lanckoroński. The King’s involvement in the work on reform was not easy, as the team was headed by his main opposition activist Ignacy Potocki, who, putting aside his animosities, decided to ask Stanisław August for his personal support. The King began work in December 1790, approving many of Potocki’s ideas, but also introducing his own corrections. Debates on the final version of the Act continued until the last minute. However, it was decided to present it to the Sejm on May 3, 1791. Opponents of the bill gathered at the Russian ambassador’s office, debating how not to get the reforms passed.

On the day of the Act’s reading the royal guards and the Dzialynski infantry regiment were prepared in advance to defend the reforms. Even cannons were brought out of the arsenal. The galleries in the Sejm hall were filled to capacity. The session was not without its excesses and drama, such as the emphatically expressed objection of the deputy Mr Suchorzewski, who had to be forcibly brought to his feet after lying down in protest on the floor of the Sejm. Finally, the king swore the Act with the words, “Juravi Deo et non poenitebit me. . . ” (I swear to God and I will not regret it. . . ) and called on those assembled to go with him to St. John’s Cathedral, where he took the oath again.

The May 3rd Constitution, known as the Government Act, consisted of 11 articles. It was the first in Europe and the second in the world, after the American constitution, to regulate the organization of state power and the rights and obligations of citizens. It took into account not only the nobility, but also townspeople and peasants. It limited the rights of the nobility without property, while the landed gentry who owned estates still maintained their privileges and sovereignty over the peasants, but in a limited form. The peasants did not gain political liberties, only the assurance of the protection of government and law, although the full supremacy of the nobility over the peasantry was maintained. Furthermore, the Act ensured personal freedom for foreign settlers and fugitive serfs. Religious tolerance was announced – but it was noted that the Roman Catholic religion was the reigning one. The Constitution also united Poland and Lithuania. Separate state institutions in Lithuania were abolished; the new constitution introduced a common army and a common treasury, and the Lithuanian nobility gained the right to fill half of the posts in the central bodies.

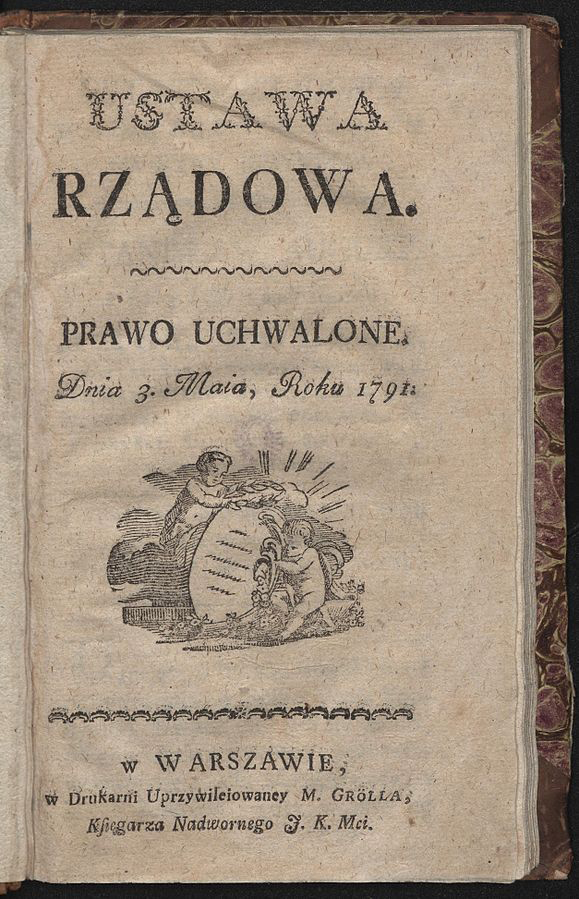

3) Pierwsze wydanie “Konstytucji 3 maja” z 1791 r., wyd. Michal Groell 1791 AD, domena publiczna / First edition of “May 3rd Constitution 1791”, publisher Michal Groell, 1791, public domain.

For the first time, the concept of the nation was introduced – citizens were to be the defenders of liberty, nationality and rights, and the project to create a 100,000-strong Polish army was accepted by acclamation. The army of the “national armed force” was to be headed by the king. Private armies were banned.

On the basis of the May 3rd Constitution, Poland became a constitutional monarchy. Legislative power was exercised by the Sejm. It remained the most important body of government, and was to be convened by the king or the marshal. Most of its deputies were noblemen (of 204 deputies, only 24 representatives of the bourgeoisie sat on the Sejm committees). All resolutions were to be passed by a majority vote, as the “liberum veto” was abolished. Confederations and resistance – armed uprisings of the nobility – were also prohibited.

The Sejm was to be “always ready,” which meant that during their two-year term, deputies could be convened for extraordinary sessions. The constitution limited the rights of the senate, leaving it only the right to veto parliamentary resolutions. The powers of the Sejm included drafting legislation and tax resolutions, as well as controlling the government and overruling its decisions. The Basic Law also reduced the dependence of the Sejm on the smaller regional assemblies (Sejmik). Additionally, every 25 years a special constitutional assembly was to meet and review the constitution.

Executive power was to be exercised by the king with a cabinet of ministers appointed by him and called the Guard of Rights, consisting of the king, the primate and five ministers: of police, seal (internal affairs), war, treasury, foreign affairs, with the heir to the throne and the marshal of the Sejm having an advisory role. Ministers could be appointed by the king from among the highest officials only during sessions of the Sejm. The Sejm could disagree with the king’s nominee and had the right to demand by a 2/3 majority vote that the minister be dismissed or face a vote of no confidence. Every act issued in the king’s name was to be prepared by the Guard of Laws and signed by the appropriate minister. The Act abolished the responsibility of the monarch. From now on, ministers were to be responsible to the parliament. Regarding the judiciary, the Crown and Lithuanian Tribunals retained the highest judicial authority. Magistrate courts for cities, and courts of appeal were established.

The Commonwealth was also becoming a hereditary monarchy. As the king officially had neither a wife nor an heir, the throne after Stanislaw August was to fall to Frederick Augustus Wettin, a descendant of the Saxon dynasty which previously ruled Poland – Augustus III. It was assumed that this would limit foreign interference in Polish affairs.

The Constitution, without fundamentally changing the nature of the state, but taking into account the interests of the rich bourgeoisie, was an important step in the development of the modern state. The townspeople of the royal cities retained the political rights and liberties guaranteed by an earlier decree: the guarantee of personal inviolability; the right to acquire and inherit land; access to offices and officer ranks; the right to ennoblement (conferring titles of nobility); the right to their own self-government; and the right to representation in the Sejm (plenipotentiaries).

The May 3rd Constitution was the greatest accomplishment of the so-called Great Sejm, and to this day is considered one of the most important legal acts in the history of Poland. Its passage was met with a great response, as it offered hope for national reform and sovereignty. However, it did not gain approval among the conservative rich magnates, who wanted a return to the old structures and even considered dividing Poland into autonomous provinces. Abroad, the Constitution was seen as a sign of bloodless state reform, while in France the monarchy had been overthrown by force and a violent bloody revolution was underway.

The May Act referred to the ideology of the Enlightenment and specific socio-political theories, mainly those of French philosophers Montesquieu and Rousseau. It established a tripartite division of political power: legislative, executive, and judicial. It abolished the exclusive right of the nobility to own land and hold public office. It eliminated several causes of anarchy oppressing the Commonwealth, such as the liberum veto, “free election” of the king by the nobles, and the age-old right of the nobility to rebellion and form confederations against the monarchy.

Author: Beata Bieniada, graduated from the Institute of History at the University of Warsaw.

English Translation: Robert Bodrog

The article was created thanks to funding from the Polish Department of Cooperation with Polish and Poles abroad of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Źródła / Sources:

Andrzej Zahorski, „Stanisław August polityk”, 1966 r.; Józef Andrzej Gierowski, „Historia Polski 1764-1964”, 1982; Sebastian Adamkiewicz, „Konstytucja 3 maja – wola narodu czy zamach stanu?”, https://histmag.org. / Andrzej Zahorski, „Stanisław August politician ”, 1966 ; Józef Andrzej Gierowski, „History of Poland 1764-1964”, 1982; Sebastian Adamkiewicz, „Konstytucja 3 maja – wola narodu czy zamach stanu?”, https://histmag.org. /

Ilustracje / Illustrations:

-

Portret króla Stanisława Augusta Poniatowskiego, malarz Johann Baptist Lampi, domena publiczna / Portrait of King Stanisław August, painted by Johann Baptist Lampi, public domain;

-

Konstytucja 3 Maja 1791 roku, malarz Jan Matejko, 1891, domena publiczna / May 3rd Constitution 1791, painted by Jan Matejko, 1891, public domain;

-

Pierwsze wydanie “Konstytucji 3 maja” z 1791 r., wyd. Michal Groell 1791 AD, domena publiczna / First edition of “May 3rd Constitution 1791”, publisher Michal Groell, 1791, public domain.

Redakcja portalu informuje:

Wszelkie prawa (w tym autora i wydawcy) zastrzeżone. Jakiekolwiek dalsze rozpowszechnianie artykułów zabronione.